Treating the Painful Kneecap

Pain behind the kneecap (i.e., retropatellar pain) is the most commonly seen injury in runners(1). This shouldn’t come as too much of a surprise when you consider that the knee flexes through a 20- to 30-degree range of motion during the first tenth of a second following heel strike, and is exposed to accelerational forces that can exceed seven times body weight. In fact, during a 5K race, the average knee must dissipate forces that exceed 650 tons of pressure(2).

Anatomically, the patella (Latin for “small plate”) is the largest of a group of specialized bones known as sesamoid bones. So named because of their shape—”sesamoid” is Latin for “sesame seed”—these bones are situated inside the tendons of strong muscles where extra force is necessary. They essentially act to increase the lever arm the muscle acts through by pulling the tendon farther away from the joint’s axis of motion. Think of them as handles on a door—if the handle were situated close to the hinges, it would take a fair amount of force to open the door. If the same door had the handle positioned as far away from the hinges as possible, it would take little effort to open the door. By increasing the lever arm afforded to the quadriceps muscle, the patella can increase force output at the knee by as much as 15 percent.

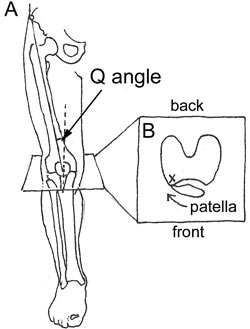

Because the body’s primary mechanism for absorbing shock is smooth deceleration of knee flexion (which is being resisted by tension in the quadriceps muscle), even the slightest problem with patellar alignment or function can cause trouble. Historically, when trying to understand and treat retropatellar pain, researchers and sports medicine practitioners have focused almost entirely on the patella itself. For example, surgeons have long believed that chronic retropatellar pain can be related to various bony misalignments, such as a high Q angle (the angle from the hips to the knees) and/or a laterally deviated patella.(See Fig. 1A.) Accordingly, numerous surgical interventions have been developed to straighten the kneecap by moving the bony attachment of the patella and/or cutting the tissue around the outside of the knee. Unfortunately, outcomes associated with these procedures have had mixed results, mainly because the bony alignment patterns that surgeons are attempting to change have not been proven to be associated with pain(3).

Furthermore, there’s a significant amount of literature showing that alignment of the patella (as measured with x-ray) and retropatellar pain aren’t correlated(4). In fact, in a recent study in which the bony displacement of the patella in 50 patients with patellar pain was compared to 47 patients who had never experienced pain, the group with painful patellae had better alignment and smoother motion patterns as measured during dynamic MRI examination(5).

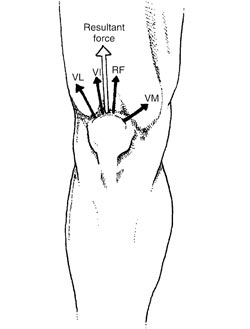

A common nonsurgical treatment for managing retropatellar pain relates to strengthening exercises for the inner quadriceps, also known as the VMO.(See Fig. 2.) Weakness in this muscle allows the patella to drift laterally and, therefore, jam into the lateral aspect of femoral condyles. (See Fig. 1B above.)

To fix this problem, various exercises have been prescribed to selectively strengthen the VMO. For more than 30 years, these exercises, which include short-arc quad extensions holding the toe out and leg presses while simultaneously squeezing with the adductors, have been the mainstay of almost all rehab programs. Although it makes sense that the VMO should be strengthened, research over the past 15 years has repeatedly shown that the standard VMO exercises do not specifically target the VMO, and make the outer quadriceps stronger(6). This worsens the alignment problem, because the patella is then drawn with even more force into the lateral femoral condyle. This explains why patients receiving no treatment often do better than patients performing aggressive VMO strengthening exercises.

The Hip Bone’s Connected to The…

Because of the poor results associated with standard rehab protocols, researchers are beginning to look beyond the knee in trying to understand retropatellar pain. Several recent studies have revealed that hip weakness is a significant factor in developing retropatellar pain(7,8). By measuring hip strength in 15 females with retropatellar pain and comparing these values to 15 females without retropatellar pain, researchers(8) demonstrated that females with weak hip external rotators and abductors were significantly more likely to develop a painful kneecap. This is important, because a few simple home exercises can easily address these imbalances. (See the photos below.)

In addition to addressing hip weakness, it’s also important to look at foot function when evaluating retropatellar pain. Although it’s frequently cited as a common cause of retropatellar pain, difficulties with measuring three-dimensional motion in the lower extremity during the gait cycle has made it difficult to tell just how strong the connection is (i.e., standard tracking markers used in three-dimensional gait studies can’t measure movement of the patella). To get around this problem, researchers at Penn State(9) surgically implanted titanium rods directly into the bones of the lower thigh, upper leg and central patella of five volunteers, who were then asked to walk on a treadmill. Special markers placed at the ends of each of the titanium rods allowed researchers to measure exactly the degree of movement among the three bones as the subjects walked with special shoes that forced them to pronate, remain in neutral position or supinate.

Although their methods seemed a little extreme (the five patients watched a video of the surgical procedure and signed consent forms before beginning the study) the researchers conclusively demonstrated that, as the foot pronates inwardly (i.e. flattens), the leg and thigh turn in excessively, thereby forcing the patella to move laterally. Before this study, it was believed that the lower leg would rotate much farther than the thigh, and the patella would not shift significantly. This research explains why custom orthotics and even prefabricated arch supports can be so helpful in managing retropatellar pain. It’s easy to do a self-examination to see if pronation is an issue for you by raising and lowering your arches while standing. If you notice your kneecaps moving in and out excessively, then you might be a candidate for orthotics.

The last issue to be discussed relates to something common among runners: overuse. If you have a hard heel strike and/or run more than 40 miles per week, sooner or later you’ll probably end up with retropatellar pain simply because the applied load exceeds the body’s ability to repair. If you’ve repeatedly been sidelined with retropatellar pain, you may want to try a few modifications in your running style, such as switching to a forefoot strike pattern and/or shortening your stride length. It’s also important to warm up slowly: all of the great Kenyan runners I know run the first mile of their training runs very slowly.

Also, because stiffness in the quadricep muscle and iliotibial band are risk factors for developing retropatellar pain(10), make sure you routinely incorporate quad and ITB stretches, and always check for asymmetries in flexibility. If your knee is currently sore, try icing the patella 4-6 times per day for 15 minutes, because sometimes the joint lining becomes inflamed and painful. Finally, you may want to consider using a simple knee brace such as the double Cho-Pat; some research suggests that, even though they don’t alter the position of the patella, small straps and even tape may effectively lessen pain. By maintaining hip strength and flexibility, controlling excessive pronation and training in moderation, your risk of developing retropatellar pain will be greatly reduced.

Home Exercises for Treating a Painful Kneecap

Figure 3) – 5 Photos

Hip strengthening exercises should be performed without pain. Three sets of 15 repetitions daily are usually sufficient. You should use enough resistance to produce fatigue.

These photographs (provided by Betty Shepherd) were modified from: Mascal C, Landel L, Powers C. Management of patellofemoral pain targeting hip, pelvis and trunk muscle function: 2 case reports. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2003;33:647-660.

References:

(1) Nigg BM: Biomechanical aspects of running. In: Biomechanics of running shoes, Ed: BM Nigg pp. 1-25, Champaign, Human Kinetic Publishers, 1986.

(2) Michaud TC, Recurrent lower tibial stress fracture in a long distance runner: a case report. Chiropractic Sports Med, 1988;2(3):78-87.

(3) Thomee R, Renstrom P, Karlsom J. Patellofemoral pain syndrome in young women. A clinical analysis of alignment, pain parameters, common symptoms and functional activity level. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 1995;5:237-244.

(4) Johnson LL, van Dyke GE, Greene JR. Clinical assessment of asymptomatic knees: comparison of men and women. Arthroscopy. 1998;14:347-359.

(5) O’Donnell P, Johnstone C, Watson M. Evaluation of patellar tracking in symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals by magnetic resonance imaging. Skeletal Radiol. 2005;34:130-135.

(6) Mirzabeigi E, et al. Isolation of the vastus medialis obliquus muscle during exercise. Am J Sports Med. 1999;27(1):50-53.

(7) Tyler TM, Nicholas SJ, Mullaney MJ. The role of the muscle function in the treatment of patellofemoral pain. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34:630-636.

(8) Ireland ML, Wilson JD, Ballantyne BT. Hip strength in females with and without patellofemoral pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2003;33:671-676.

(9) Lafortune MA, Cavanagh PR, Sommer HJ. Foot inversion-eversion and knee kinematics during walking. J Orthop Research. 1994;12:412-420.

(10) Witvrouw E, Lysens R, Bellemans J. Intrinsic risk factors for the development of anterior knee pain in an athletic population. A two-year prospective study. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28(4):480-489.

- Posted June 18, 2008

© Copyright 2008-2022 by Take The Magic Step®. All Rights Reserved.